MONTEVIDEO, Uruguay, Dec 12 (IPS) – Last month, the Saeima, Latvia’s parliament, passed a package of eight laws recognizing same-sex civil unions and related rights. The new legislation came in response to a 2020 Constitutional Court ruling that found that same-sex couples have a constitutional right to the benefits and legal protections afforded to married opposite-sex couples.

Equal marriage rights are still a long way off, and civil unions are only a first step in the right direction. But in one of Europe’s most restrictive countries on LGBTQI+ rights, activists see this as a significant shift, one that has come about after numerous attempts over more than two decades. Anti-rights forces agree, and they won’t let it happen quietly. They have already responded by attempting to prevent the new law from being passed by campaigning for a referendum.

The breakthrough

The first Civil Partnership Bill was introduced by the National Human Rights Office in 1999, but was rejected by Parliament’s Human Rights and Public Affairs Committee and was never debated. Initiatives gained momentum in the mid-2010s, but all were rejected – the latest attempts came in 2020 and 2022.

On October 29, 2020, a popular initiative calling for the adoption of a civil union law, which had collected more than 10,000 signatures, was voted down by parliament. Campaigners immediately launched a new initiative for the ‘legal protection of all families’, which attracted more than 23,000 signatures – but that was also rejected by parliament in December 2022.

However, after the 2020 parliamentary vote, two court rulings brought about change. In November 2020, the Constitutional Court ruled that the Labor Code was unconstitutional because it did not provide for parental leave for the non-biological parent in a same-sex relationship.

As a result of a 2006 anti-rights initiative to ban same-sex marriage, the Latvian Constitution defines marriage as a union between a man and a woman. However, the concept of family is not explicitly defined in relation to marriage, and the court interpreted it more broadly as a stable relationship based on understanding and respect. It concluded that the constitution required protection for same-sex partners and gave parliament a deadline of June 1, 2022 to change the law to provide a way for same-sex couples to register their relationship.

A year later, in December 2021, the Supreme Court ruled that if the deadline was missed, same-sex couples could resort to the courts to have their relationship recognized.

Counter-reaction to rights

The anti-rights backlash started quickly. Two months after the Constitutional Court ruling, Parliament introduced a constitutional amendment that went beyond ratifying the definition of marriage as between a man and a woman, defining the family as based on marriage.

To comply with the Constitutional Court’s ultimatum, the Ministry of Justice submitted a draft law on civil unions in February 2022 and two months later, despite an attempted boycott to deny a quorum, Parliament passed its first reading .

When it became clear that the court’s deadline would be missed, same-sex couples began petitioning the court for recognition as a family unit. On May 31, 2022, the first of dozens of positive statements was made.

That same day, a close parliamentary vote resulted in the appointment of Latvia’s first gay president. Momentum increased, and on November 9, 2023, parliament finally passed a law allowing civil unions between people of the same sex.

But conservative politicians have managed to suspend the new law as they try to gather the signatures needed to force a referendum they hope will prevent it from coming into effect.

A long way to go

Even if she survives the challenge, the new law is not a panacea. Ultimately, access to marriage is the only way to ensure that LGBTQI+ couples have the same legal rights as heterosexual couples. Recognition of same-sex relationships is a step forward, but still leaves Latvia behind neighboring Estonia, which legalized same-sex marriage in June.

If the new legislation is enforced, registered same-sex couples will gain some, but not all, of the rights associated with marriage. They are entitled to hospital visits and tax and social security benefits, but not inheritance rights or the right to adopt children.

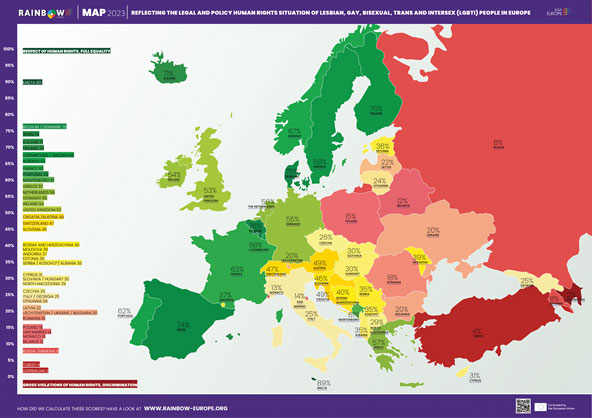

Outside the legal sphere, the biggest challenge will be influencing public opinion, as shown by Latvia’s scores on Equaldex’s equality index. This ranking combines a legal index that rates key laws and a public opinion index that measures attitudes toward LGBTQI+ people. Latvia scores much lower in the area of public opinion than in the area of legislation. A special 2019 Eurobarometer survey found that only 49 percent of Latvians believed that LGBTQI+ people should have the same rights as heterosexuals.

The message is clear: changing laws and policies will not be enough – and any legal victories will remain in jeopardy unless social attitudes change.

Latvian LGBTQI+ organizations are fully aware of this and have therefore been working on both fronts for years. An important part of their work to combat prejudice is the annual Pride event, which Latvia pioneered for the Baltic region in 2005. As the organizers say, Latvian Pride grew from 70 participants who faced 3,000 demonstrators in 2005 to 5,000 participants in the EuroPride 2015, which was held in 2015. in the Latvian capital Riga, and 8,000 during the 2018 Baltic Pride, also held in Riga. Pride was repeatedly banned by the Riga City Council, and consistently faced hostile counter-protesters – but fewer and fewer, while the number of Pride participants grew, boosting people’s self-confidence.

Global trends show that progress towards the recognition of LGBTQI+ rights far outweighs regression. Latvian LGBTQI+ advocates will continue to make progress both in policy and awareness. They will continue to work to secure what they have already achieved, while striving for more. They are on the right track.

Ines M. Pousadela is CIVICUS Senior Research Specialist, co-director and writer for CIVICUS Lens and co-author of the State of Civil Society Report.

Follow @IPSNewsUNBureau

Follow IPS News UN Bureau on Instagram

© Inter Press Service (2023) — All rights reservedOriginal source: Inter Press Service